Since the times of the great Giotto, who was given credit for equaling in terms of value and mastery the works of the ancient Greek and Roman masters, the desire to revive the magnificent art of the past started to spread in Italy. Ancient Rome had long been the center of the civilized world, and in the hearts of the Italians the desire to revive a glorious tradition, taking inspiration from the teachings of the masters, was burning intensely. Thus began the Renaissance, a new era marked by a great artistic revolution, destined to be spread throughout Europe. This era of incomparable splendor saw art reach the peak of perfection.

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, talents such as Brunelleschi, Donatello and Masaccio were born in Florence, a rich mercantile centre. The sixteenth century was the century of great Italian artists such as Michelangelo, Raffaello, Tiziano, Leonardo da Vinci, and Benvenuto Cellini. As the historian Ernst H. Gombrich observes, it is not possible to know how so many masters were born in the same period, giving rise to a unique artistic magnificence. “The birth of genius cannot be explained. It is better to just enjoy it”.

It was precisely in Italy, during a period of such artistic and intellectual prosperity, that the history of Renaissance jewelry began. In particular, in the second half of the fifteenth century, when the rest of Europe was still tied to the conventions of the Gothic, a goldsmith’s art among the most creative in the world flourished in Italy. There were numerous materials used for the creation of splendid jewels: gold, silver, gemstones, pearls, leather, wax, silk and linen. Unfortunately, since just a small amount of those marvels has survived to us, the best way to investigate the history of the Reinassance jewelry is to observe the portraits of the nobility of the time. Indeed, the ruling classes loved to be portrayed while wearing luxurious jewelry to flaunt their wealth and their high social rank, and to express several different values and meanings.

Proof of the Renaissance jewelry, as well as its symbolism, is given by the famous Italian painter and architect Raffaello Sanzio. In his painting Portrait of Maddalena Doni, the depicted gentlewoman, belonging to the upper Florentine middle class, is wearing garments made of precious fabrics and precious jewels, among which stands out the marvelous pendant in gold, on which are laid a ruby, an emerald, a sapphire and a pearl, elements which symbolize purity and marital fidelity. By observing attentively the jewel, it can be recognised the figure of a small unicorn enveloping the emerald. If on the one hand the mythological creature is a symbol of chastity on the other the emerald, gem of Venus, the goddess of eros, represents a wish for fertility.

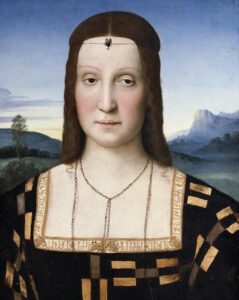

Jewelry could represent the intellectual qualities of the wearer. The emblem of such symbolism is another fascinating painting executed by Raffaello, Portrait of Elisabetta Gonzaga. Wife of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, Elisabetta was not only considered as the ideal of beauty of her time, but also a woman with great culture and intellect. It is interesting to focus on the sublime jewel, worn on her forehead, in the shape of a scorpion: on the one hand, the animal represents the virtue in opposition to the violence (legend has it that scorpions kill themselves whenever they are in danger), on the other hand, the diamond, placed in this position, represents her sharpness of mind.

Equally fascinating is the painting Ideal Portrait of a Woman, executed by the legendary Italian painter Sandro Botticelli, famous for having created some of the most enchanting female images in the Renaissance. An interesting anecdote tells that his nickname refers precisely to the goldsmith’s art. In fact, according to contemporary Giorgio Vasari, Alessandro Filipepi’s nickname would derive from Botticello, a goldsmith in whose workshop he was trained. In the painting, the jewels of the young woman, identified as Simonetta Vespucci, muse of the artist, are depicted with extraordinary precision. A great number of pearls adorns the hair of the noblewoman, who is wearing on her neck a cameo finely painted, emblem of the widespread passion for the ancient Roman cameos, object of great interest for the humanists of that time. Renaissance Italy mastered the creations of cameos inspired by antiquity.

“The works of the past are like flowers from which bees get the nectar to make honey”, wrote poet Petrarca. The rediscovery of classical treasures and the revival of the ancient artistic tradition in all its forms, is also shown by another outstanding painting by Sandro Botticelli: La Primavera. The work, a triumph of grace and beauty, was placed in the residence of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, the cousin of Lorenzo il Magnifico. There are represented nine figures from classical mythology, including Venus in the centre. The goddess is wearing a necklace whose shape recalls an ancient jewel worn by the Roman women as a fertility amulet: the lunula. The three Graces, maids of Venus, are wearing instead marvelous brooches, a perfect example of Renaissance jewelry. They are made of enameled gold leaves, pearls and gemstones.

Certainly, the courts of noble families such as the Medici in Florence, the Sforza in Milan and the d’Este in Ferrara, where the best artists and writers were welcomed, promoted a great artistic growth. “It was truly a golden age for people of genius”, wrote Giorgio Vasari in 1568. The fashion of the time was dictated by influential women like Isabella d’Este, considered by many as a true “influencer ante litteram”, and Eleonora di Toledo, an icon of elegance and great lover of pearls, as showed in the work by Agnolo Bronzino who depicts her with her son Giovanni de’ Medici wearing plenty of them, as symbol of purity.

Not only in Italy, but also in the courts of all Europe, an increasing passion for jewelry of exceptional beauty spread. In particular, thanks to the discovery of the New World, gold, as well as diamonds, pearls and gemstones became increasingly fashionable within the European ruling classes. Christopher Columbus found enormous resources off the Venezuelan coasts during his sailing to America in 1498. Around 1500, were found huge quantities in the Aztec temples and palaces, destroyed by Hernàn Cortès and his army. Spain led the gold trade.

In England, jewels were flaunted with great abundance in reference to the immense splendor of the kingdom. Henry VIII, upon his death, owned ninety-nine diamond rings and an immense wealth of precious jewels. Elizabeth I, his daughter, is always depicted while wearing numerous pearls and diamonds. The people of that time rarely owned precious ornaments. However, the social and sentimental importance of jewels was universally acknowledged.

The King of France, Francis I, fascinated by the Italian Renaissance, invited to his court some of the best artists including Leonardo da Vinci, Benvenuto Cellini and Matteo del Nassaro. He had a strong passion for hat jewelry, or enseignes, one of the most characteristic jewels in the Renaissance, of Italian origin and dating back to the mid-fifteenth century. France had no equal in the production of miniatures within splendid medallions, that could have both celebratory and sentimental value.

The figure of the Renaissance artist craftsman and the enhancement of his social status are particularly interesting. If in the classical age, the work of hands was somehow considered humble, less worthy than the use of the intellect, men like Leonardo da Vinci and Benvenuto Cellini proved quite the opposite. During the Renaissance, the artist became a true Master, a noble figure “who could not achieve fame and glory without exploring the mysteries of nature and researching the secret laws of the universe”, as Gombrich wrote. They were no longer just workshop owners, but also men of great knowledge, able to increase the magnificence and harmony of the world with their art.

Nowadays, the excellent artistic talents who more than anybody else embody the beauty and the strength of our tradition (which is our biggest wealth and our greatest teacher) deal daily with difficulties and threats, and their voices, unfortunately, are often left unheard. The artists craftsmen of our time should return to being central, like the masters of the past. Together, we should restore great dignity to art, to craftsmanship, to our identity. It is precisely now that, more than ever, we should be inspired by the profound ideal of rebirth and love for the past which marked the peak of the cultural splendor of our society: the Renaissance.