the story of the enfant terrible between madness and genius

Aggiungi traduzione in Italiano

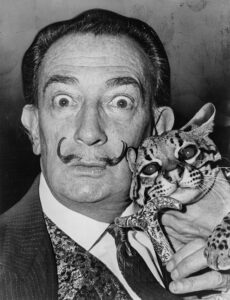

“At the age of six I wanted to be a cook. At seven I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily ever since”. Salvador Dalí was born in Figueres, Spain, in 1904. Every morning while getting up, he would say “I experience an exquisite joy —the joy of being Salvador Dalí.”Brilliant, eccentric, caustic, at times crazy, Dalí has always exceeded limits since his youth. In 1926, at the age of twenty-two, he was expelled from the San Fernando Academy of Art in Madrid due to impudent behaviour towards his professors. And in his life, he has never hidden his enfant terriblepersonality.

Admirer of contemporaries Picasso and Mirò, but also of Raphael, Rubens, Dürer, Vermeer and Velazquez, from whom he inherited the distinctive long and curled mustache, Dalí developed a unique artistic style based on extraordinary contrasts, mysteries, illusions and symbols. All spiced-up with a distinctive irony and a marked taste for excess. He launched art in a field uncharted till then: the deepest psyche. In fact, around the 1930s, Dalí joined the surrealist avant-garde movement in Paris, composed of innovative artists who loved to represent a world of imagination, fantasy, mystery in which nothing was as it seemed. Art was ruled by the dimension of unconscious, where any limitation of reason was abolished, in favor of whimsy and irreverence, key to more and more exuberant works of art. “We are all hungry and thirsty for concrete images. Abstract art will have been good for one thing: to restore its exact virginity to figurative art.” Stated Dalí. Even Sigmund Freud, whose psychoanalysis theories were a great source for surrealist art, was so fascinated by Dalí that he went beyond investigating the art originated from the one he called “a serious psychological problem”.

Surrealism soon became the most influential movement in XX century. But Dalí never conformed. Neither from an artistic nor a political point of view, so much so to lose in a few years his fellows’ approval. “The difference between me and the surrealists, is that I am surrealist”, he declared candidly. In those years, Dalí created some of his most well-known works, including The Burning Giraffe, Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening, Metamorphosis of Narcissus, Swans Reflecting Elephants and lastly, the most representative of all, The Persistence of Memory. In the latter, are present several typical symbols of the Dalinian universe: the melting clocks, which represent the oppression of time, the stretched face with very long eyelashes, the insects. His innate talent allowed him to achieve quickly international fame. “There are some days when I think I’m going to die from an overdose of satisfaction”, Dalí once said.

“During the Renaissance, great artist did not restrict themselves to a single medium. The genius of Leonardo Da Vinci soared far beyond the confines of a painting”. Dalí, calling himself “paladin of a New Renaissance”, has always refused to set limits on his art and his interests spanned from painting to sculpture, science, photography and several other disciplines, such as cinema. In fact, he collaborated with famous film directors, such as Luis Buñuel and Alfred Hitchcock. In short, his life was a whirlwind of madness and exuberance, antidote to monotony. He also became passionate about fashion: how can we forget the iconic collaboration with the stylist Elsa Schiaparelli? A unique extravagant match, two eccentric personalities whose creativity proved to be complementary and gave birth to works of art that have signed the history of fashion. Among these, the white silk dress decorated with a red lobster, the skeleton dress, the famous shoe-shaped hat with the heel facing upwards, the amazing suits with pockets shaped as drawers. Dalí even created four covers for Vogue.

The artistic genius also realized extraordinary jewels. “Benvenuto Cellini, Botticelli, da Lucca created decorative gems, chalices, glasses, cups and bejeweled ornaments of puissant beauty.” These are the names of the well-rounded artists who inspired him. Dalí deeply loved gold, which he considered as a sacred material, a celebration of the soul and a sign of purity. After all, “In jewels, as in all my art, I create what I love”. Besides gold, his works are an explosion of diamonds, rubies, pearls, emeralds. Dalì wanted his jewels to inspire spiritual ecstasy in the spectator. Among the most magnificent ones, you can admire the Royal Heart, a mechanical jewel that reproduces the incessant beating of a heart, studded with rubies. It was created in honor of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II of England. The element of the heart was also used to create his Honeycomb Heart jewel, which represents the sweetness that “is in the heart of every woman”. The same extraordinariness is given by the Ruby Lipsjewel which reinterprets the poetic cliché of lips in a surrealist key. Also worthy of attention are the Telephone Earrings, in gold, diamonds, rubies and emeralds: “The ear is a symbol of harmony and unity; the telephone design a reminder of the speed of modern communication – the hope and danger of instantaneous exchange of thought”. Even in jewels, the artist expresses his personal view of the universe by undertaking the paths of metamorphosis, imagination, illusion. As in the jewel The Persistence of Memory, drawn from the famous painting. Even the Eye of Time jewel, made of paltinum, rubies and diamonds, represents a gaze on the present and future, referring to the ambiguity of time, which cannot in any way be overwhelmed. Who wouldn’t recognize Salvador Dalí’s signature in the visual effect of the Tree Of Life work? The gold and diamond necklace is actually a precious trunk from which an anthropomorphic-inspired face hangs. “(These jewels) were created to please the eyes, uplift the spirit, stir the imagination, express convictions.” However, “without an audience, without the presence of spectators, these jewels would not fulfill the function for which they came into being.”

In conclusion, as long as there is an audience, Salvador Dalí’s art will continue to live: “The viewer is the ultimate artist”. Thus Dalí, celebrating the subjective interpretation, still shows us the inexorable energy of the human soul creativity, unique in its complexity, in opposition to the coldness of the laws of rationality. Precisely this energy is the reason why these works are destined for eternity: because they involve, astonish, amaze, scandalize, upset and deeply touch humanity, without respecting any rules and forgetting the time of a bygone era. In words of the great visionary Dalí “I have a Dalinian thought: the one thing the world will never have enough of is the outrageous”.